27,000,000: the estimated number of human

trafficking victims in the world

1644: the

estimated number of US beds available to trafficking victims

You do the math.

Housing options for trafficking victims are severely

limited nationwide. According to a Polaris Project survey, there are a total of

529 documented beds designated for trafficking victims, and another 1115 that

are offered to trafficking victims among other vulnerable populations. A total

of eight of these beds are in Illinois.

This is no small problem.

Last week the Cook County Human Trafficking Task

Force hosted a Housing Summit in order to connect key agencies that provide

housing and shelter options for vulnerable populations like trafficking

victims. The Summit sought to identify the gaps in the existing systems and to

begin the long-term discussion on innovative ways to tackle them.

Challenges

in the current system

The needs of trafficking victims are complex and

diverse. Domestic violence shelters, homeless shelters, and other temporary

care systems have been viable resources, but they are often not equipped to

provide the protection and trauma-based care that trafficking victims need. A

lively discussion at the Housing Summit last week pinpointed the abundant

challenges.

When providing support and resources for

trafficking victims, a major obstacle is the diversity of the populations. Trafficking is a phenomenon that

transcends socio-economic, educational, gender, age, and background differences,

leading the victim services needed to be equally diverse. A safe setting for

one victim may not be a wise option for another, a prime example being a victim

needing protection from a perpetrator, necessitating security, confidentiality,

and distance. Nonetheless, this type of setting cannot be provided for every

victim, especially in open-access homeless shelters. A soft bed does not always

equate a safe place.

Another frustration with the current system is

the disorganization of resources and

collaboration. First responders are not guaranteed a secure next step in

regards to social service agencies because there is not an organized protocol

nor centralized database for the various resources available to trafficking

victims. Each agency is dependent on its own connections, none of which are

ultimately responsible for the trafficking victim’s placement.

This concern overlaps into apprehension about

some agencies’ lack of experience with

trafficking victims. Safe bed providers – shelters, private families, and

prison cells (yikes) may not have trained staff who understand the flight risk

of trafficking victims, the trauma-based care needed in all communication with

victims, and the safety needs – both physical and psychological – of the

victims. Direct service providers express concern that faith-based supporters

and other well-meaning individuals may not advocate a victim-centered approach

to care and may not have a firm grasp on how to deliver trauma-based care.

In the most practical of concerns, social

service providers also highlight difficulty with transportation of clients to the shelters. Independent agencies may

be responsible to accompany trafficking victims anywhere from two miles to 200,

depending on the location of the shelter. Public transportation may not be an

appropriate option, and there is no streamlined response to this need. While

calling 311 is an option, the service obligates a visit to a police station or

a medical center before offering transportation. Moreover, given the tension

between law enforcement and victims (many of whom have been mistreated by law

enforcement officers, may have been threatened with deportation, or may have

been denied help in the past) as well as between law enforcement and social

service providers, this is an unattractive option. Social service providers

have found the bureaucratic requirements involved in attaining permission from

the Department of Human Services to take advantage of 311 transportation

services to be more of an obstacle than helpful.

In the same vein, bureaucratic hoops regarding documentation for victims have proven

to be destructive to obtaining safe housing for trafficking victims. Many

victims lack 1) documentation at all, 2) matching documentation, or 3)

documentation of legal status. Shelters are unable to verify victims’ ages,

creating liabilities that they often cannot afford. They may not be able to service

undocumented individuals or they may have other clientele requirements that bar

particular trafficking victims from receiving care.

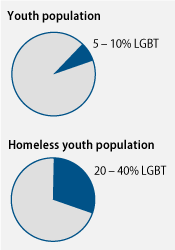

Some trafficked populations face more obstacles

than others. Particularly under-resourced groups are trafficked males, trafficked transgender populations, and

labor-trafficked populations (in contrast to female sex trafficking victims).

Many of the presently utilized safe beds are for victims of domestic violence,

which may be appropriate placements for female victims of sex trafficking. Few

shelters have the necessary protection for male victims, and even fewer have

appropriate options for transgender or transsexual victims. Placing a

trans-woman in a male shelter, for example, can have traumatizing effects. Cook

County lacks safe spaces and trained staff for these populations.

To that effect, a lack of “flexibility and common sense” on behalf of the shelters

has presented unnecessary challenges in obtaining safe housing for trafficking

victims. Treatment varies not only from shelter to shelter, but from staff

person to staff person, and the lack of continuity has been a primary

frustration for social services seeking provision for trafficking victims.

This list of concerns is far from exhaustive.

Looking

ahead

While the problem is daunting, the Cook County

Human Trafficking Task Force and supporters are ready to wrestle the issue. The

Housing Summit last week began the dialogue on potential responses to these

challenges through innovation and collaboration.

Participants in the Summit discussed the

physical shelter and housing options. Currently utilized are shelters for

victims of domestic violence, for youth, and for people who are homeless, though

some of the shortcomings are detailed above. Hotels also have potential for

emergency placements, especially in strategic partnership with supportive

hotels. An option for transitional housing is private family placements, which

involve extensive training and liability for the families agreeing to offer

shelter or housing to victims. For long-term placements, there are innovative models

of scatter-site housing as well as communal living. There are many

possibilities to continue exploring.

Participants also discussed the need for stages

of change and providing housing for all three levels of need: emergency,

transitional, and long-term placements. Particularly highlighted was potential

for a tiered system of services to account for each level and stage of need, as

well as for the diversity of trafficking victims’ profiles (age, gender, sexual

orientation, legal status, familial status, type of trafficking, and more).

The Summit suggested improvements to the current

system of response as well as the creation of new resources and new shelters

specifically for victims of trafficking. Potential funding opportunities were

also brought to the forefront to prioritize the coordination of trafficking

victim resources.

This is just the beginning of the discussion.

The Cook County Human Trafficking Task Force and the Summit participants will

not rest until assured that human trafficking victims have safe spaces to the

do the same.

The

Housing Summit is just one component of the Task Force’s efforts to improve

services to trafficking victims. We envision a strategic network of law

enforcement and social service providers able to meet the various needs of each

victim.

Alexa Schnieders

Program Development Intern